News

John Mellencamp To Celebrate Decades Of Hits Ahead Of 'Dancing Words' Tour

Wall Street Journal: The Chain-Smoking Rock Star Who Made Indiana Football Hurt So Good

John Mellencamp Set To Perform At The Primary Wave Music Pre-Grammy Party to Celebrate 20 Years Presented by VENU

Ogunquit Playhouse Announces Small Town The World Premier John Mellencamp Musical Oct 1 - Nov 1, 2026

People.com John Mellencamp Announces Greatest Hits Tour with Some Help from Pal Sean Penn and a 'Jack & Diane' Sing-Along (Exclusive)

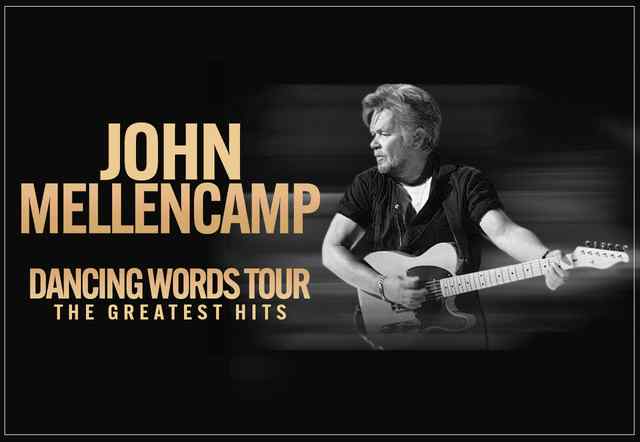

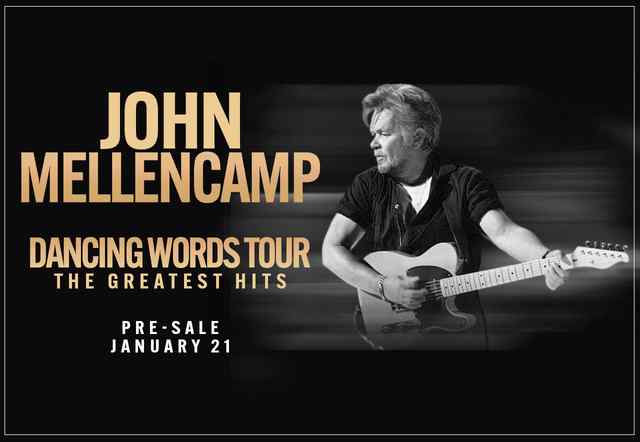

John Mellencamp Sets Landmark Dancing Words Tour - The Greatest Hits

Watch John On The Joe Rogan Experience

APNews.com: Minutes to Memories: John Mellencamp rolling Out Jukebox Of His Old Hits

Mellencamp.com John Mellencamp Dancing Words Tour The Greatest Hits Pre-Sale Ticket Details

Dancing Words Tour The Greatest Hits VIP Packages Ticket Details

Billboard: UME’S Bruce Resnikoff Honored, John Mellencamp F-Bombs Antisemitism At Ambassadors of Peace Gala 2025

Spin Magazine: The 40 Greatest Musicians of The Last 40 Years

The Commercial Appeal: John Mellencamp, Martina McBride honor Memphis music during Hall of Fame ceremony

Memphis Music Hall of Fame Announces Special Guests for September 25, 2025 Induction Ceremony

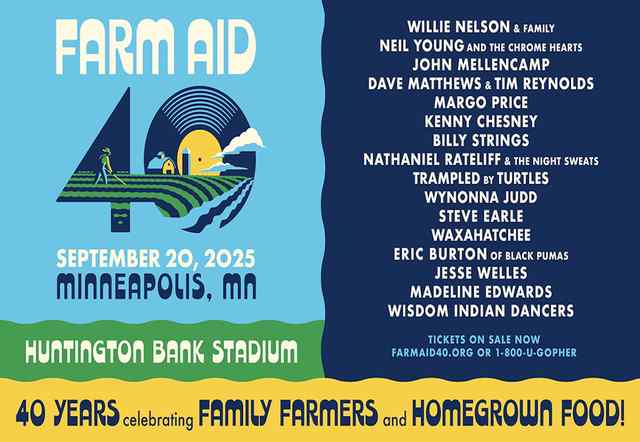

The Minnesota Star Tribune: How Willie Nelson and John Mellencamp created Farm Aid

Homelessness and Mental Illness Today

Kenny Chesney, Wynonna Judd and Steve Earle Join Farm Aid 40 Lineup of Hall of Famers

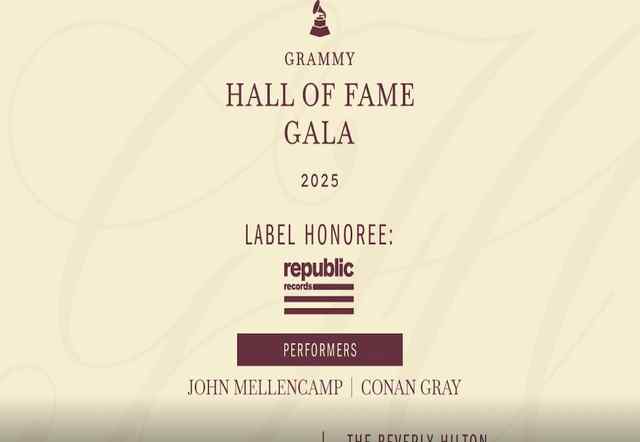

John Mellencamp Honors Republic Records at Grammy Hall of Fame Gala

Farm Aid To Kick Off Year-Long 40th Anniversary Celebration With Minneapolis Music and Food Festival Sept. 20th

Conan Gray & John Mellencamp To Perform Republic Records Tribute At The 2025 GRAMMY Hall Of Fame Gala

John Mellencamp's Museum Exhibitions To Be Represented By PANART In Landmark Partnership

Listen to select songs as read by John Mellencamp