The Washington Post: John Mellencamp Would Like You To Behave. Or "Don't Come To My Show"

The Washington Post by Chris Klimek

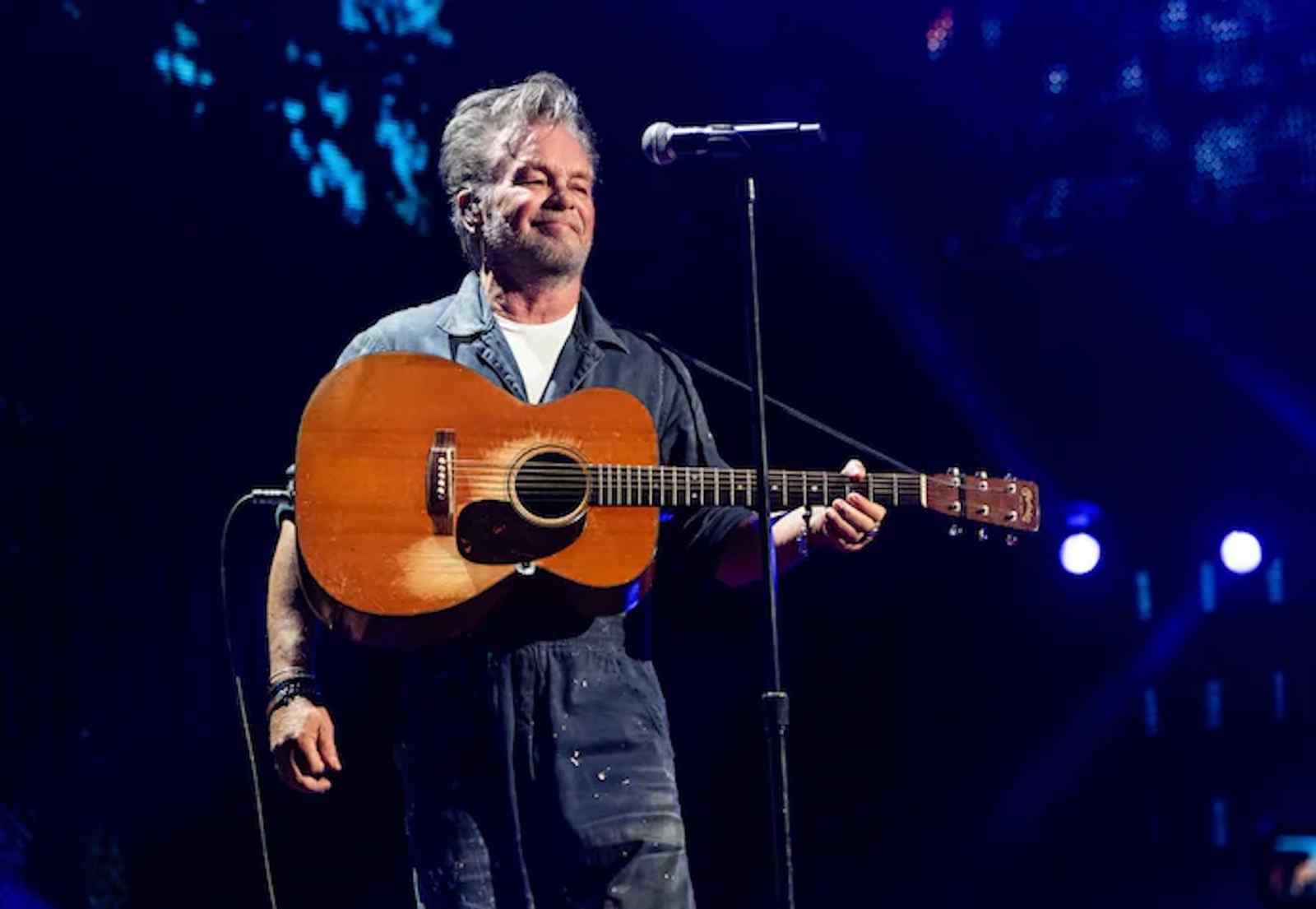

John Mellencamp is a septuagenarian, a thrice-divorced grandfather and a chain smoker. He’s a liberal activist and a painter who’s never moved out of ruby-red Indiana. He’s a boomer rock star with a bunch of contemporaries in the grave. He’s quit the music business who knows how many times and is back on tour now, offsetting deathless hits like 1982’s “Jack & Diane” (“Hold on to 16 as long as you can”) with death- obsessed latter-day songs like 2008’s “Longest Days” (“Sometimes you get sick and you don’t get better”).Last month, he walked offstage after being heckled at a concert in Ohio (though he returned to finish his

set). Someone who’s never read an interview with the legendary musician might speculate that he’s

reached his temperamental dotage, but a closer character study suggests Mr. Mellencamp has always been

this capricious.

“I’m 72, and I’m still doing a teenager’s job,” he said, chuckling, during a recent Zoom interview.

He says his peers who are still at it are just as surprised by their longevity as he is by his own. Though they

seem to be fewer and fewer.

“I’ll be working out today with an iPod and a song will come on and I’ll go, ‘Well, that [expletive] guy’s

dead. This guy’s dead. What happened to this guy?’”

Here’s what he knows for sure: He’s not going to pitch a tour to play one of his best-loved old albums in its

entirety, a la Bruce Springsteen and U2. So don’t look for a 40th anniversary roadshow of his quintuple-

platinum-selling 1985 landmark “Scarecrow” next year, or one for its triple-platinum 1987 follow-up “The

Lonesome Jubilee” in 2027.

“It just hits me sideways,” he says.

And he won’t be coming to an arena near you.

In 2009, the year Mellencamp toured minor league ballparks with Bob Dylan and Willie Nelson (with

whom he and Neil Young organized Farm Aid, an annual concert to raise money for farmers, staring in

1985), folk legend Pete Seeger gave him a crucial piece of career advice: “Keep it small, but keep it

going.”

Which is why most of Mellencamp’s appearances in the D.C. area over the last 15 years have been at the

3,700-seat Constitution Hall, where he’ll perform again on April 18.

“As soon as [Seeger] said that, it all clicked in my head,” Mellencamp says. “Quit worrying about if you’re

going to [expletive] sell all 20,000 seats. Go play places you know you’re going to sell out.” A smaller

room makes audiences more tolerant of the unfamiliar, he says, though his set list is still heavy on the hits.

Mellencamp started singing in a band as a teenager in Seymour, Ind. When he first went to New York to

seek his fortune in 1974, he was as interested in painting as in singing. (Even now, he still paints almost

daily.) After several Hoosierville-to-the-Apple long hauls dropping demo tapes at every record label or

management firm he could find an address for, he got a lousy deal, a risible but seemingly indelible stage

name in “Johnny Cougar” and an unmemorable first few albums.

It wasn’t until his fifth, 1982’s “American Fool,” that Mellencamp began to find his voice as a songwriter,

scoring his first and only U.S. No. 1 in “Jack & Diane.” On its follow-up, 1983’s “Uh-Huh,” the Artist

Formerly Known as Johnny Cougar was at last able to use his family name, becoming John “Cougar”

Mellencamp for his most commercial era.

He remained an innovative but reliable hit maker throughout the 1980s, landing 10 songs in the Billboard

Top 10. More significantly, he smuggled then-uncool instruments like accordions and violins — and lyrics

that foregrounded their political and existential discontent more audibly than many of his peers in that

feather-haired era — onto MTV and FM rock-radio playlists: “Rain on the Scarecrow,” “Paper in Fire” and

“Check It Out” have all remained set list staples over the decades.

By the time he was finally able to drop “Cougar” altogether, the 1990s had dawned. And though

Mellencamp continued to make good records and score hits — his cover of Van Morrison’s “Wild Night”

with D.C. native Meshell Ndegeocello lodged itself in the Top 40 for most of 1994 — he spent the decade

railing against the fact the culture was passing him by, cussing out (and, on at least one occasion, punching

out) label guys who couldn’t figure out how to make his hip-hop-curious Clinton-era albums sell like his

Reagan-era ones had.

Once Mellencamp finally accepted that he was no longer a mainstream musician, he experienced a creative

rebirth, teaming up with producer T Bone Burnett for a pair of stripped-down albums. 2008’s “Life, Death,

Love and Freedom” was as somber and persuasive as a deathbed confession. He followed it up with 2010’s

even more willfully primitive “No Better Than This.”

Though he’s continued to release albums of mournful but nourishing new music — two in the last three

years, in fact — you won’t hear much of that material in his show. In his approach to curating his deep

catalogue for the stage, Mellencamp was always more a Tom Petty than a Springsteen, nestling new or

unfamiliar songs in among road-tested favorites and tending to stick to the set list rather than calling

audibles. “I toured with Dylan for a while and he didn’t play any [expletive] songs that anybody

recognized,” he says. “I thought, that’s too extreme. So it’s a fine line of what should be recognized and

what should be kind of challenging for the audience. And I think the audience who likes music, they like

the idea of being challenged a little bit.”

Of course, with Mellencamp, there are always contradictions. Including to his own edicts, like the one

about booking only smallish venues. Later this year, he’ll play 15 outdoor dates on the Outlaw Music

Festival Tour with his longtime Farm Aid fellows and ’09 ballpark tour mates, Willie and Bob. But when

he isn’t sharing the bill with other headliners, he’s sticking to theaters.

And he’d like some decorum.

“I do expect etiquette inside of the theater, the same way you would at a Broadway show,” he says. “My

shows are not really concerts anymore. They’re performances, and there’s a difference between a

performance and a concert. Look, I’m not for everyone anymore. I’m just not. And if you want to come and

scream and yell and get drunk, don’t come to my show.”

April 18 at 8 p.m. at DAR Constitution Hall, 1776 D St. NW. darconstitutionhall.net.